There are two 125-year-old houses in Eliot that are going to be demolished if the neighborhood doesn’t rally to save them. The best option would be to purchase them from the developer who owns them, Guy Bryant of GPB Construction, or failing that, to convince him not to tear them down to build his ultramodern 40-foot-tall rowhouses that, needless to say, don’t fit in to the neighborhood. The houses were built at the time the City of Albina was its own city.

623 NE Thompson St. was built in 1889. Its first owner was Louis Nicolai, whose early contributions to the city led to the naming of Nicolai Street in Northwest Portland, where he and his brothers had their factory. Also named for him: Nicolai Ridge, Nicolai Road, and Nicolai Mountain, an outdoor recreation area in the Columbia River Gorge. At the time Nicolai had the house built, Albina was a red-hot real estate investment area following the completion of the first Steel Bridge in 1888 that finally allowed easy travel between Portland and Albina, with beautiful houses going up all over. Only a few of these homes have survived.

Mr. Nicolai likely built the house as an investment, as he was a savvy businessman who worked in a variety of fields. He was, at the time, the president of the Portland Cracker Company, aside from continuing his work as an owner of the Nicolai Brothers Sash and Door Company, a large factory that occupied the entire block between 2nd and 3rd St. and Couch and Davis in Northwest Portland.

It probably sounds humorous today to take so seriously, but back then, the various cracker and biscuit companies were in a state of war. Eventually they began to consolidate their operations as one company took over another, and the Portland Cracker Company absorbed several, becoming in the process Pacific Coast Biscuit Company.

Eventually all the companies consolidated, ending the feisty cracker and biscuit wars, and became the National Biscuit Company, or what we today know as NABISCO.

Back to 1889. Mr. Nicolai was in the process of building a large new house on NE Holladay St., located probably where the Lloyd District Burgerville is today. It is quite possible he lived at his investment property, 623 NE Thompson St., while this house was being completed. It is also possible, given later city development, that 623 NE Thompson St. is the last house that still stands that Mr. Nicolai owned or lived in.

Back to 1889. Mr. Nicolai was in the process of building a large new house on NE Holladay St., located probably where the Lloyd District Burgerville is today. It is quite possible he lived at his investment property, 623 NE Thompson St., while this house was being completed. It is also possible, given later city development, that 623 NE Thompson St. is the last house that still stands that Mr. Nicolai owned or lived in.

After Nicolai departed the property for his newly built, larger permanent residence on Holladay, the house at 623 NE Thompson (then 429 Eugene St., prior to the street renaming in 1931) bounced back and forth between various real estate speculators and investors. One prominent and well-connected man named William Reidt owned it twice — he was both its third and fifth owner. On his first outing as owner, he resold it for a huge profit that was likely fraud. Reidt ended up convicted of fraud, but was pardoned by the governor.

In 1895, the house acquired its first long-term resident, and oh what a colorful character he was. His name was John M. “Jack” Roberts.

Back in those days, port cities of the West such as Portland, Seattle, and San Francisco, were wild and dangerous. This was the era of shanghaiing and unexplained disappearances of sailors. It took a very tough breed of night watchman to deal with the crime lurking about on the waterfront, and Roberts was one of those men. Officially, he wore a police star, but he was not paid by the City. (His brother, Griffith “Griff” Roberts, was a fully sworn officer of the law and in the employ of the City of Portland.) Rather, at that time, store owners, bar owners, and brothel owners paid the salary of Special Policemen like Roberts to deal with miscreants who got out of hand, which happened frequently.

The machinations of keeping order were not without corruption. In 1903, Jack Roberts became the subject of an indignant outcry from the saloon keepers and brothels owners who paid his wages. They said he was ordering full-scale police raids on saloons and women who did not comply with his orders to hand over protection money. The ensuing scandal dominated the talk of the town for some time.

Roberts, once under this microscope, declared under oath that he was simply following orders when he asked for protection money and that he was not personally ordering the police raids, nor could he, as a lowly watchman command other officers. He suggested that his orders came from far, far above, even extending to Mayor Williams’s office. (George H. Williams was 32nd Attorney General of the United States, the Chief Justice for the Oregon Supreme Court, and a United States senator from Oregon. His national political career was cut short by scandals, so he continued to work in local politics until his death in 1910. In 1905, he was indicted along with the Chief of Police for failing to enforce gambling regulations – another protection racket.)

However, when it came time to hold anyone accountable, only Jack Roberts received any blame. He was found guilty and was, in essence, the fall guy. There are indications that further backroom deals were being made, though, because he received as punishment only a brief suspension and returned to work shortly thereafter, being given back his Police Star so he could legally arrest people and check them into the City Jail while working his position as a night watchman.

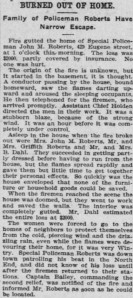

It was a year later, on December 22, 1904, when, it was reported, a streetcar conductor on his way home from work between 1 and 2 a.m. saw flames from beneath a house. He instantly ran to the house and began pounding on the door, awaking the occupants, who included Jack’s brother Griff. The whole family was able to make it out before the smoke killed anyone, which was a complete miracle in and of itself. Once outside, they had to watch the house burn as the horse-drawn fire brigade came. They arrived when the interior was beyond salvaging, but the house still stood, and so they went to work saving the walls.

Was it an accident? Payback? Was it a threat? Attempted murder? Was the miraculous appearance of the unnamed streetcar driver in fact a ruse, and the intent was to burn the house to terrorize the inhabitants without physically harming them? Was his unexpected appearance one of the luckiest breaks of all time? We will, in all likelihood, never know.

But the house survived, and was rebuilt. As was the case with many building fires of the era, everything not burned to the point of weakness was simply reused, so the house today still holds the scars it endured on a cold night 110 years ago.

Even though physically unharmed, it surely struck a deep psychological wound to the family members. Jack Roberts, who wasn’t even home at the time, proved to be a bit hair-trigger on issues involving fire in later years. In 1910, Special Policeman Roberts called in the fire department over a case of smoke from a ham in an oven.

Even though physically unharmed, it surely struck a deep psychological wound to the family members. Jack Roberts, who wasn’t even home at the time, proved to be a bit hair-trigger on issues involving fire in later years. In 1910, Special Policeman Roberts called in the fire department over a case of smoke from a ham in an oven.

While an event of unspeakably awful proportions was avoided that Christmas of 1904, the house — and family — also saw their share of tragedy. Two of Mrs. Roberts’s brothers, who were likely staying or living with their sister at the time in the home, died as young men, and their funerals were held in the house. One, Charles P. Stahl, drowned at age 25 while playing at the beach in Seaside on July 20, 1902. The second, Benjamin H. Stahl, died in 1908 aged 23 in what was likely a logging accident. Logging was then a terribly dangerous profession that took the lives of tens of thousands of young men in the Northwest.

After an eventful two decades, the historic record goes silent on events at the house. It seems Mr. and Mrs. Roberts’s later years were less terrifying, or at least we hope. The house was sold again in 1923 after nearly 30 years of occupancy and history in the Roberts and Stahl families.

While no written record of it has yet been uncovered, there was an enticing bit of history that made its way into the house during this time: an underground speakeasy. Prohibition in the United States commenced in 1920; Roberts had struggled with alcohol throughout his life and was quite familiar with underworld figures. It made sense that he’d have chosen to keep such a place on his property.

It took a bit of extra knowledge from a friend familiar with the history of underground clubs in Northeast Portland over the decades to identify the speakeasy, but once you see it, it’s obvious. The clearest elements of a speakeasy contained in the house at 623 NE Thompson Street are:

- An outside door leading to the basement that can be isolated from the main house. There are two doors in the back of the house, one of which leads to the main floor and one of which leads directly to the basement. There is also a doorway in between where you can close off access to the main house from the basement. This allowed the family living on the property to conduct themselves normally while an underground club carried out its business.

- A “Police Raid” warning button. At the top of the steps there is a very old, currently nonfunctional button that could have been hit by someone coming down from above to warn others.

- And, most obviously: A secret trap door through which liquor could be passed. In the bathroom on the main floor, there is what appears to be a built-in storage bench. The bench has a false bottom that can be removed, upon which a passage to the basement appears. Anything 1′ x 2′ or smaller can easily be lowered surreptitiously to the floor below.

Can we afford to lose this unique piece of Portland history?

The foregoing information represents a few weeks of searching for its history. Just a few weeks. I have a pile of names of owners over the decades yet to research, and I’m sure there are so many more stories, so many more families, so many more generations that have their histories tied up in this historic home. This old house is a thread in the very fabric that makes up the Eliot neighborhood, the history of Albina, and the city of Portland, and its loss would be an extraordinary blow.

633 NE Thompson next door to 623 is also headed for demolition if the neighborhood doesn’t rise to fight it. The home was built in 1890 by Bates E. Hawley, who lived there for three years and then departed for Kelso, where he found success as an inventor, patenting a new type of bolt and screw connection.

The house’s second owner, Charles Sven Rudeen (who gave his name as Swan C. Rudeen in his early years in America), began his time in Portland as an immigrant butcher from Sweden and eventually became Chairman of Multnomah County Commissioners, where he was involved in various historically significant events. He lived at 633 (orignally it was 435 Eugene) for quite some time, and ultimately built his new home with his wife Hilda and their children next door, at 2309 NE 7th Ave. in 1908. The fact that these two properties were, over 100 years ago, owned by the same person is a part of the problem posed by new construction today: the longtime Eliot homeowners at 2309 NE 7th Ave. have found out the lot line is located under their concrete driveway and they may lose some of it to the jackhammer when (let’s say if) this demolition and large new project occur, because a century back no one felt a need to assure that the driveway of Charles’s new 7th Avenue house wasn’t partially over the lot line of his other property.

In 1917, after 24 years’ residence in the houses next to each other at 633 NE Thompson and 2309 NE 7th, Charles and Hilda moved to a 1914-built house at 3425 NE Beakey St. This home sold for over $1 million in 2012 and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Sadly for the properties they left behind, though, a major oversight occurred in creating the Eliot Conservation District: 623, 633 NE Thompson, and 2309 NE 7th Ave. were left off.

Roy Roos helped with the information in this article. Many of the dates came from Roy’s 2008 book, “The History of Albina.”

Reblogged this on Oregon Real Estate Round Table.

LikeLike

Great article on the history of these historic homes. It would be a shame to see them demolished.

LikeLike